This is the second of three posts summarizing my recent chat with New York Jets legend Don Maynard. The first post focused on advantages he gained from modified equipment. We now examine the explosive Jets passing offense of the 1960s. The third post looks at the 1968 New York Jets and their win in Super Bowl 3.

Painting by Robert Hurst. www.ADamnFineArtist.com

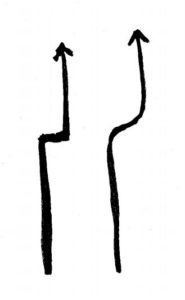

ROUNDING OFF

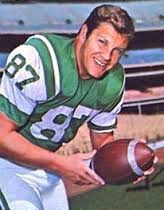

Maynard broke into pro football with the New York Giants in 1958. He played behind Frank Gifford and Kyle Rote as a running back and receiver. He also returned kicks and subbed as the fifth defensive back. “Besides Gifford, I was probably the most all-around ball player they had,” Maynard said.

Don paid attention to how Gifford and Rote ran pass routes and modified their actions. For example, Maynard noticed that when a receiver cuts sharply, he grants the defender an extra second while he stops to cut. Maynard rounded off his routes to keep his momentum going.

The Jets had a “staircase” pattern. A receiver ran several yards, cut across, and flew downfield. Maynard’s rounding approach not only sustained his momentum, but also left turning defensive backs flat-footed. That extra second gave Maynard a head start breaking deep. Huge gains off the staircase helped Don set the NFL record for most yards per catch, a mark he still holds. He graciously points out, however, that it’s for players with over 600 catches and Lance Alworth owns a slightly higher average with 542 grabs.

KEEPING AN EYE ON THE BALL

Don frequently practiced catching with one eye closed. “Often during a game you’re only seeing the ball out of one eye. If you’re running a down and in, you’re only seeing the ball out of your left eye,” he explained. Maynard would have several balls thrown from different angles during practice, catching the ball with one eye closed.

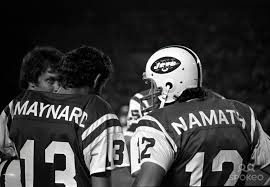

FLASHING SIGNS

“I taught Namath something that no coach, even in today’s game, has ever taught a quarterback to do: read the defender!” Maynard exclaimed. Pre- and post-snap adjustments were key elements to the Jets success. Receivers employed hand signals before the snap to notify quarterback Joe Namath of changed pass routes. Acting like one was digging with a shovel signaled a down and in; (D-I for dig; D-I for down and in.) Other signs included placing either an open hand or a fist on a knee, one or two hands on the hips, and patting the top of the helmet. Each movement signified a different pattern. The Jets used this system at the line of scrimmage like baseball teams use “steal” signs.

Maynard and tight end Pete Lammons often lined up on the same side. Lammons would run 10 yards and in, and Maynard 15 and in. Teams using zone defenses couldn’t cover both men in the same area. Often the speedy Maynard was left isolated in man-to-man coverage, resulting in big plays.

SUMMARY

Maynard, Lammons, and George Sauer suited up with Namath for several consecutive seasons. Together, they practiced nuances of the passing game every single day. Their tireless work led to outstanding execution on the field.

The Jets passing attack reached a pinnacle in 1967. Namath became the first quarterback in pro football history to throw for 4,000 yards (4,007). Maynard and Sauer finished 1-2 in the AFL for receiving yardage, with Don averaging over 100 yards per game.

NOTE: Maynard details more of the Jets passing game and his life story in The Game before Money. Two above quotes are from that book.

Permalink